Section 1 sets out “Our Inheritance of Faith”. Actually, this is a bit of a misnomer, because it really says more about who we are than about what we believe. I’ve already indicated that the term “communion” is a little fuzzy in the proposed Covenant, and we see this in section 1.1.1, in which the Churches affirm their “communion in the one holy catholic and apostolic church.” I don’t think I disagree with the affirmation; I’m just not entirely certain exactly what it means. I think it might mean that we each claim to be part of the “one, holy, catholic and apostolic church” (the RCs might disagree with that, I suppose) and that we acknowledge that none of us is the whole church - that there are other parts of that one church that are not part of the Anglican Communion. Maybe that’s what it means. It clearly can’t mean that we are all “in communion” with the whole church because, sadly, we aren’t.

It’s the next bit that attracted the only question in A Lambeth Commentary. Section 1.1.2 starts out well enough. We all affirm the faith which is found in the Scriptures and attested to by the creeds. But the question asked at Lambeth was why the “formularies of the Church of England” were referenced here. The question asked and answer given are as follows:

Q: What is meant by “historic formularies of the Church of England”?

A: There are certain texts, of varying degrees of authority, which were crucial in the formation of Anglican identity from its early days. However, not all of these (notably the 1662 Prayer Book) have played a direct role in the development of the ecclesial life of all the Provinces. Although we wish to emphasise the value of our common traditions and to pay careful attention to the historical roots of the Anglican family, we recognise that Provinces relate to these formularies and traditions in different ways, and will attend to this question in the next process of drafting.

With respect to theological discernment and teaching, the CDG agree with the comments of bishops that further clarity is needed on:

- the teaching role of bishops and synods;

- the role of the laity in relation to scholarship and bible study;

- the role of reason in relation to Scripture and Tradition

- the need to recognise up front that the mission into which we are invited is God’s mission, empowered in us by the Holy Spirit.

The Covenant Design Group is committed to further work to refine this section in light of comments received.So the Covenant Design Group acknowledged that these “historic formularies” are seen differently in the different Churches of the Communion. Certainly the 1662 Book of Common Prayer hasn’t been used in Canada for nearly a century, in the United States for over two centuries and in Scotland ever, for example. And many Churches have long since moved to newer prayer books as the de facto norm for their worship, even if the 1662 BCP or some version of it retains status as the official prayer book.

My question is why the proposed Covenant suggests that the “historic formularies ... bear authentic witness to [the] faith.” (emphasis mine) My problem here is with the use of the present tense. These formularies were, according to the proposed Covenant, “forged in the context of the European Reformation” and it seems to me that they can only be properly understood in that context. By taking them out of their own context and placing them in our context today we make them try to speak to a context that their drafters could never have contemplated.

I don’t argue that the prayer book and the 39 Articles weren’t authentic witnesses to the faith in their day. Nor do I suggest that they have nothing to say to us today. But I do question whether decontextualizing these documents is fair either to the documents themselves or to us. I imagine most Anglicans would have very little interest, for example, in participating in a Commination service. (Many Anglicans would be surprised to discover that such a service ever existed!) And whilst the language of the 1662 wedding service sounds awfully quaint at first blush, many would blush for real at the mention of “men’s carnal lusts and appetites, like brute beasts that have no understanding.”

As to the 39 Articles, they are best understood as orienting the Church of England within the controversies of the 16th century. Although they continue to say some useful things, many, if not most, Anglicans would disagree, for example, with Article 37's endorsement of the death penalty. And the claim that “the Bishop of Rome hath no jurisdiction in this Realm of England” is both patently false today and irrelevant to the other Realms comprised by the Communion.

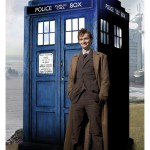

The formularies really should have been left in their own context rather than transported into ours as if by a Time Lord.

Taking things out of context is confusing.

Taking things out of context is confusing.Speaking of context, the next four clauses quote the Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral. Context is important here, too, because it seems a lot of people have forgotten it. It’s common for some people to suggest that the Quadrilateral would be perfectly adequate as a Covenant. It certainly does mention the bare-bones essentials. We have the Scriptures, the Creeds, the dominical Sacraments, and episcopacy. What else do we need? The point here, though, is that the Quadrilateral was not developed as a definition of what it means to be an Anglican Church; it was developed as a minimalistic definition of what it means, from our perspective, to be an authentic church of any kind. The Quadrilateral was developed with the idea that we might want to negotiate “Reunion” - or merger - with some other Church at some point and we would need a basic measuring stick to determine whether such other Church met the minimum requirements of authenticity. They would certainly have other features, but they would have to have these four or there would be no point talking to them. So, for example, there would be no talk of merger with congregationalist churches because they have no episcopacy. (Whether Presbyterianism is a legitimate local adaptation of episcopacy would have to be determined.) And we certainly couldn’t merge with teetotalling Methodists who use grape juice instead of wine for communion! (And, incidentally, the Orthodox Churches don’t fit the Quadrilateral exactly, because they don’t have the Apostles’ Creed. It’s a Western creed.) Still, there’s nothing to argue with in the Quadrilateral. We’d better all fit into it or we don’t even meet the minimal requirements of an authentic Church.

Finally, section 1.1 mentions our “shared patterns of common prayer and liturgy” and participation in mission, which is shared with other Churches. Which brings us full circle.

Based on these basic affirmations, section 1.2 has the signatories commit to a whole lot of care in the use of scripture, especially in “theological and moral reasoning” in our varying contexts. (Section 1.2.2) Section 1.2 really reflects the context of the dispute in the Communion that the proposed Covenant is supposed to address. But it’s not clear how we’re meant to account for those “varying contexts” or if the tension between them is supposed to be resolved or allowed to be creative. In fact, the question of context - cultural, political, geographic, temporal and even psycho-social - is fundamental to our current disputes. It shapes our lives as Churches, it shapes our understanding and incarnation of the faith, and it shapes the proposed Covenant.

In setting out the fundamentals of the faith, Section 1 pays lip service to context, but it really doesn’t seem to be aware of the implications of context for how we might be able to live out the same faith in different ways in different contexts, and how we might be able to build creative relationships across the apparent boundaries of our different contexts.

...many would blush for real at the mention of “men’s carnal lusts and appetites, like brute beasts that have no understanding.”

ReplyDeleteIf I were present, rather than blush, I'm afraid I'd laugh out loud as I'm doing right at this moment.

Romantic, isn't it? :-)

ReplyDeleteMy Son is, reasons known only to himself, is a Southern Baptist. I am a card-carrying Episcopalian. My favorite Niece is Russian Orthodox. Our Faith in Jesus is unshakable...but, a tad diverse. We can't even agree how to "cross" ourselves. The term for this is practicum. Now back to a statment I made earlier. The focus of Faith should be only on Jesus. What is important are His teachings and his offer of redemption. To attempt any other solutionary argument weakens the Power of faith and, thus (as Kerkegaard said) the grounding elements of Self.

ReplyDeleteMy understanding is that the words were largely nicked from the CofE declaration of assent which is phrased as it is to fudge the issue of whether or not people believe the 39 articles and BCP today.

ReplyDeleteI know you're not suggesting it, Bill, but in case anyone misreads my comments about who might or might not fit the Quadrilateral, I'm not suggesting that anyone else (Presbyterian, Baptist, Orthodox) is anything but a perfectly good, faithful Christian. The Quadrilateral would be inadequate as a test of faithfulness in Christ. Rather it is a test of whether another Church is sufficiently compatible with Anglicanism to consider merging. The idea that the Orthodox might not squeak in because of the Apostles' Creed reveals the inadequacy of the Quadrilateral, not any deficiency in Orthodoxy.

ReplyDeleteAnd, yes, you are quite correct that the focus of our faith is God Incarnate in Jesus Christ.

Alan, you're quite right. Canon C15 is footnoted in the text of the proposed Covenant. Still, whatever the source, a present-tense reference to "historic" formularies takes them from their own context into ours. Let them speak in their own context, as we must do in ours.

ReplyDeleteActually the Orthodox do fit inside the definition. The creed mentioned in the quadrilateral is not the Apostles' Creed but the Nicene.

ReplyDeleteMy Orthodox family members are not sure we fit because of our et filoque error. :-)

2. The Nicene Creed as the sufficient statement of the Christian Faith.

A minor point in the scope of your otherwise excellent analysis but worth making so we do not insult and of our Eastern cousins.

FWIW

jimB

In the 1950s in England there were serious ecumenical discussions between the CofE and some Nonconformist Churches (even though they got off on the wrong foot when Archbishop Fisher called on everyone else to join the normative CofE).

ReplyDeleteOne reason (amongst several) they foundered was summed up in the complaint that the CofE was clear about the fundamental necessity of the episcopacy but no two members could agree on what the episcopacy was.

Please look again at this point in the quoted CDG material:

ReplyDelete* the role of reason in relation to Scripture and Tradition

Then look very carefully at 1.2.2 in the 'final' covenant. "Moral reasoning" there means "moral determination". It is NOT "reason" as in Hooker's "Scripture, reason, and tradition". 1.2.2 opens up a path for magisterium.

Now trace this from the Windsor Report draft through the Nassau draft to the St. Andrew's draft. It's a very subtle theological coup.

Despite what was said the CDG following Lambeth 2008 sat on its hands.

For more see

http://home.roadrunner.com/~billhammondsr/church/srtAndCov.html

Thanks, Jim. I have absolutely no interest in insulting our Eastern cousins. They are perfectly fine Christians with a rich and deep tradition. Nevertheless, you are quoting the Chicago Quadrilateral. Lambeth Resolution 1888:11 chose to add the Apostles' Creed to the clause, so it reads as quoted in the proposed Covenant: "The Apostles' Creed, as the Baptismal Symbol; and the Nicene Creed, as the sufficient statement of the Christian faith." As I suggested above, the problem here is with the Quadrilateral, not with Orthodoxy. No Anglican would suggest that the Orthodox Churches are anything but authentic Christian churches.

ReplyDeleteFilioque is another story. FWIW, we in Canada dropped it from the Nicene Creed in the eucharistic rite of the 1985 Book of Alternative Services, pursuant to Lambeth resolution 1978:35 (note: not "et filioque" the -que suffix means "and" in Latin.)

William, I am sure that you are correct that "reason" in 1.2.2 is not Hooker's use of the term, and on this point it does appear that the CDG didn't develop the issue as they said they would in the Commentary.

ReplyDeleteI personally wonder if some of the deficiencies in the proposed Covenant text are simply a result of the extreme, and in my view undue, haste of the drafting process.